Since late August, I’ve worked with the 3rd/4th graders on their writing once a week. At the suggestion of their teacher, we jumped into a form of writing that was new to me with this age group, development of a fictional character and creating a story around that character. In the past, I generally stuck with personal narrative, since it’s easier to become a writer when content is known and based on personal lived experience. With this group, however, we thought it would be worth a try. It’s been an eventful endeavor, to say the least.

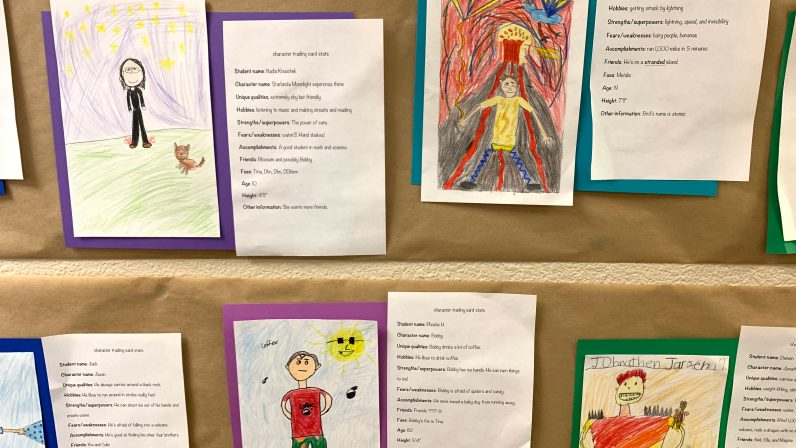

We’ve worked on developing the characters themselves, looking at both inner and outer characteristics. Although each character initially was required to have mostly human qualities, they were allowed one super power. Writers were required to include strengths and challenges, accomplishments, quirky qualities, and secret fears. As we moved through the process, it became clear that some writers had developed wild adventures for their character, yet hadn’t yet fully described the actual character. In order to bring forth this information, each child created a “trading card” of his/her character. Now fully illustrated, you can see these characters displayed on the wall in the hallway.

Once this step was completed, the task was to make sure the information was inserted into ongoing drafts, so readers would be more familiar with the actual character. Several students passionately wrote pages and pages about their character. When we sat down to confer about their writing, it was apparent that, as a teacher, I had more to do. I could see we needed to talk about story line. I researched how to teach story line to young writers and found an approach called SWBST developed for just this purpose. It involves five words, each with a question:

Somebody – Who is the main character?

Wanted – What does the main character want?

But – What is the problem or conflict?

So – How does the problem get solved?

Then – What is the result or outcome?

What I could see is that many of our young writers next need to focus on what the main character wants. This has created a powerful shift in helping them sort out which writing serves the story line, and which is a distraction or diversion. I used the metaphor of a railroad track, keeping the train moving forward. Focusing on what the main character wants has helped some writers celebrate the ways in which they’ve kept their story moving forward. It’s also been informative to those who have yet to uncover their story line.

In the midst of this process, I had a conversation with a teacher from another class about the 3rd/4th graders’ writing. We talked about our daily work to know students individually, how they move through the world, how they learn, and how we can best serve their needs. As I was describing our exploration of the concept of story line, it dawned on me that it’s not unlike what we do with our students each and every day. Each of them is a character, and our days are devoted to discovering each of their story lines. We ask ourselves what each of them wants as a human being, then work together remove obstacles and offer guidance as they find their way.